In 2015 the New Statesman’s Kate Mossman published a article on Bruce which is still shared amongst the Hornsby community today. Kate approached her subject in a completely different way to how we were accustomed she was exceptionally knowledgeable, which always brings out the best interviews from anyone – and her piece was superbly observed.

Kate has become well-known to the Bruce community in the subsequent three years, and I thought it would be interesting for her to look back on that interview. She didn’t disappoint… Kate sent this over this tremendous account:

“I only truly discovered Bruce Hornsby about eight months before forcing myself upon him in Williamsburg for this interview. I’d been a music journalist for eight years by that point. Being a “fan” always brings you to the job – but then it becomes a job: your personal tastes remain personal, and the bulk of your commissions aren’t people you choose to listen to in your own time.

The route to Bruce was unconventional: the scene in The World’s Greatest Dad where Robin Williams stays up overnight to write his son’s “fake suicide note”. Shadowhand played as the sun broke over Williams’ stubbled face with a time lapse effect. A small plastic robot rattled across his desk. What new young indie band is responsible for this beautiful song on the soundtrack, I asked myself?

I asked him, then, about the mad left-hand part in the “ “King Of The Hill”, secretly hoping he might show it to me on one of the three grand pianos pushed up against each other in the studio, and he did.

I did know about Bruce, though. At seven, I’d heard a busker playing The Way It Is outside the National Gallery in Edinburgh and had been rooted to the spot for the tinkly bits. I knew that he’d played piano on I Can’t Make You Love Me, which had rendered me a teary mess at eighteen. When I looked into multiple versions of Shadowhand on Youtube after seeing the film, years later, I found him playing with one of my musical heroes Bela Fleck; then performing with Jerry Douglas and Chris Thile, the first musicians I ever interviewed, at Telluride Bluegrass Festival. He was the DNA joining together much of what I’d been listening to my whole life, and I couldn’t believe it all came together in one person. There was nothing to do but binge it: for three months I floated around London with my headphones on. Then travelled to Troy, NY, in the winter to see him do a solo piano show. A few months later, I decided to combine my rediscovered teenage enthusiasm with my job, and try to interview him. I asked him, and he seemed to be up for it.

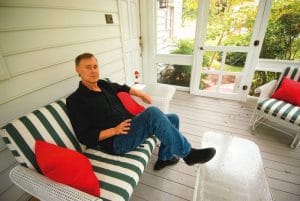

The town of Williamsburg vibrated with “Bruce energy” in little hidden clues. In a student diner near the William and Mary College, there was a faded cutting from Rolling Stone or Q from the eighties with a picture of him in his garden, arms folded, and the caption: “Bruce owns this land”. There was a Christian Science reading room nearby. I took a cab to Jamestown and went on the model of the ship The Susan Constant, thinking about Black Rats of London. I walked on to the car ferry used in the video for Valley Road, and took it across the river and back, pressing my earphones into my head so I could hear the song against the wind.

That night, I returned to my hotel and sat in the bar with a pint starting to feel oppressed. I had dozens of questions for my Bruce Hornsby interview in the morning, divided up into six categories like “Childhood” and “Relationship to eighties hits”. I always memorise my questions for interviews: reading them off a bit of paper seems detached and rude, like an NME journalist from the Seventies. I never get nervous before an interview, unless it’s someone I particularly admire.

The next day arrived, and I pushed personal nerves down to another part of my brain. Which is not to say that the two-or-more hours I had at Tossers Wood didn’t pass in a rather heightened, hyper-real state. Bruce emerged from the balcony in his sportswear – he kind of floated down the stairs. Kathy gave me a diet coke in the kitchen. I asked them both whether the creek outside was tidal (why?). Bruce showed me his books. Then we moved into the studio, where the first thing he did was pick up his vintage Casio, saying something like, “You’ll know this”, and played the first part of Shadowhand. He had no idea that the song had been my way into his music, so it all seemed a bit magic. At the start of the interview, he played the Dulcimer too. I’ve got clips of it on my phone, being tuned up. I’d mentioned how much I liked “Miami”, which hadn’t been released yet, and he did a quick rendition. It felt more “interactive” than some interviews I’ve done.

But with a musician you seriously admire, I think you’re secretly hoping for more than that: a brief connection that goes some way to replicating the excitement you’ve felt absorbing their work. I asked him about those musical “goosebump” moments – the “levitate” moments – that anyone who truly loves music understands. I’d had my own, most recently, with the live version of Country Doctor from Bride of the Noisemakers: specifically, the guitar solo, and the way the drums come in. It always felt to me like trying to land a small aircraft in a strong wind: Sonny’s drums pushing up against Doug’s falling guitar, and a feeling of almost nauseated excitement. I told Bruce that I’d “over-listened” that bit of Country Doctor, that it didn’t “work” any more. He said: “Give it a rest, come back to it and it will”.

I liked that he assumed a level of knowledge from me about his material, as it allowed me to push to more geeky areas that fans would be interested in. I found myself asking what had happened to his left hand in the 1990s. He told me he’d locked himself away and worked on it. I asked him, then, about the mad left-hand part in the “ “King Of The Hill”, secretly hoping he might show it to me on one of the three grand pianos pushed up against each other in the studio, and he did. Knowing I was a geek, he then directed me towards the editions of his teenage zine Piano Monthly in the William & Mary College Library. I went to find them the next day.

I’d not booked a taxi back from his house because I didn’t know how long the interview would go on for. This, I realised with shame, potentially left me stuck there. Perhaps fearing the afternoon might never end, Bruce took matters into his own hands and got his car keys, driving me back to my hotel in town. I was childishly excited about that: shotgun with Bruce

in Bruce’s town. I wound up in the hotel bar a few minutes later, nursing another pint, my questions asked, navigating a monumental adrenalin slump.

The experience changed my way of working. I wrote that particular piece in the spring evenings when back in London, and unlike with some articles, every line was fun to think about. I wanted Tony Millionaire, who’d done the artwork for the Dead’s “Dave’s Picks” live series, to do a cartoon for the New Statesman, and he filed just two hours before we went to press. I’d said something about “this musical maverick pushing himself out into unchartered waters”: he sent me back a piano in the middle of the sea, with musical notes circling it like seagulls.

I stopped reviewing records, and live shows, whenever possible, and turned full-time to what I enjoyed – long-read profiles – instead. I was reminded that with space and depth you could make music journalism a truly creative experience again, which was the reason I’d got into it in the first place. I went to Moscow with Kiss, and tracked down the damaged eighties icon Terence Trent D’Arby. I didn’t care much about their music, but the deeper you look into a story the bigger the story is. I spent three days in Florida with the Trans-Siberian Orchestra, wondering why their founder Paul O’Neill had wanted me to write about his legacy, until just a year later, he died in the same hotel the band had put me up in.

The artists overlooked by the mechanical rounds of the British music press have the best stories to tell. It sounds corny, but I was glad that the creative energy that I felt in Bruce’s music could be converted into something creative in my life, too. I’m not sure I’ll find another subject like that again though.